Garden Edition: Gardening with Perennials: May and June

by Linda Coyner

The popularity of perennials continues to outpace that of annuals. Home gardeners and professionals have taken to them enthusiastically, and with good reason. Garden centers can't seem to unload the trucks fast enough. That wasn't always the case: raised eyebrows met my suggestion to include perennials in a corporate landscape ten years ago. Resistance to this idea, in part, was concern about perennials requiring a different kind of upkeep than shrubs and trees traditionally needed. Now, of course, the use of perennials is commonplace. Black-eyed susan (Rudbeckia), purple cone flower (Echinacea), ornamental grasses, hypericum (Polyphyllum) and astilbe, to name a few, now soften the hard edges of many corporate landscapes.Gardeners new to perennials are likely to find the terminology confusing, at best. For instance, the terms tender and hardy are used in referring to perennials and you might wonder those terms don't form an oxymoron. After all, wouldn't all perennials be considered hardy since they return every year? Not necessarily. Your area's climate plays a big role in whether a perennial shows up next year for an encore. A hardy plant is said to need no winter protection. A tender one may not survive the winter, although some can survive the cold with protection.

Another term often used in connection with perennials is herbaceous, a term that means a plant that develops soft leafy growth that comes and goes with the seasons, unlike the ever-present woody growth on shrubs and trees. Some woody plants, however, are used like perennials--pentas, lantana, clematis, cotoneaster, and hydrangea, dwarf spirea--but are actually shrubs; you could call them woody perennials.

A few perennials have evergreen foliage, which sounds like a contradiction. Hellebores, euphorbias, bergenias, and iberis are examples. Their foliage shrivels but endures as the temperatures drop. If placed strategically in the garden, such plants can play a part in the winter landscape.

Don't confuse perennials with biennials, which are plants that usually need two years to bloom. The first year's growth is all foliage; the second year's growth brings on the flowers and then they die. Sometimes biennials get mixed up and take one year or even three years to do this. Common examples of biennials are foxglove [photo left], sweet william, and canterbury

bells.

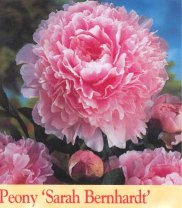

Despite the vagaries of language, everyone knows that perennials are a good investment for homeowners. They're worth the extra cost at the cash register because, unlike annuals, they come back year after year. But is that true? The hard fact of life is that perennials come back, but some come back longer and more reliably than others. Most, though, need the gardener's help. A few varieties have proven themselves amazing self-sufficient and long-lived; just look at the flowers around old, abandoned farm houses. Alongside overgrown lilacs and forsythia, you're likely to find clumps of rhubarb and sprigs of asparagus with perennial flowers like peonies

iris, and day lilies. Keep in mind that they're the exception. Most perennials live only a few years unless the gardener intercedes to clone or otherwise ensure future generations.Finding the value in a perennial is a matter of extending its life through offspring. Typically, a healthy plant reaches maturity after about three to five years and then starts to decline. While the plant is at its peak, you can make the most of your investment by reinvesting earnings, that is, multiplying the plant by division or taking cuttings. Sometimes, it's possible to start new plants from its seed. Each perennial variety, though, has its own preferred method for multiplying. For example, division works best with plants like day lilies, iris, and hosta. Sea thrift (Armeria), goat's beard (Aruncus) , and some ornamental grasses don't divide easily and should be started from seed. Most woody plants can only be increased by cuttings.

Division is the most foolproof method. It allows you to start new plants from chunks of an established plant. The best time to do this is spring. If your climate has a long, warm fall season or mild winter, you might be able to divide plants in early fall and still get them well established before winter.

An overcast, cool day is ideal for dividing plants but if the day turns out to be warm and sunny, be sure to shade the new plants or they'll die from wilting. Start by cutting back the tops of the plants you want to divide by one half to two thirds. This compensates for the root mass that is inevitably lost. Then lift out as much as the plant's root mass as possible and you're ready to divide. I use an old kitchen knife or a heavy-duty weeding knife I bought at Smith & Hawken. (I see it's now available from A.M. Leonard/www.amleo.com as item #4750 for $10; a clip-on sheath is $5.). For a large root mass typical of hostas, I go at it with a sharp shovel or even an ax.

Don't worry about destroying the plant. Plants seem to be very forgiving. Just make sure there a bit of top growth with each root section. Of course, the sooner the divisions get into the ground the better. If it's not possible to accomplish this right away, hold them over for awhile by keeping their roots wet and the plants out of direct sun.

Cuttings work best for woody stemmed or creeping perennials. Snip off 4- to five inch shoots. Remove lower leaflets and dip into rooting hormone. (The white powder will stick better if you wet the shoot first.) Insert the coated end of the cutting into potting soil, moisten, and cover with a plastic bag. Place the pot or tray in bright, indirect light. Inspect the cuttings every couple days and remove molding leaves and shoots. Sometimes cuttings will root in water, something I've recently done with pentas[photo left]. Either way, it may take a few weeks before roots appear so be

patient.There are entire books devoted to starting plants from seeds but it doesn't have to be complicated. My brother-in-law showed me how easy it was to start seed inside and I've been doing it ever since.

Gathering and using seed from the parent plant is fun and the way I prefer but it's not always possible to get the exact variety of the parent plant. That's because seeds from hybrids won't breed true to the variety. (If you're determined to have a particular variety, use seed from a seed company.)

A seed-starting mix is necessary to prevent rot and bacteria, conditions that are a common cause of failure. Fill the trays with the soil mix and sprinkle the seed on top of the mix. Cover lightly with more soil mix and then with plastic, placing the tray in indirect light. Once the ground warms outside (to plant tomatoes, as an example), it's safe to start the trays of seeds outside. When starting seeds inside, fluorescent lights and bottom warming cables are needed; a bright window sill usually won't do.

Another way to safeguard your investment is with regular maintenance, which can prolong the life of your plants and extend their flowering season. In addition to regular fertilizing and watering, make a point to tour the garden frequently. Observe its condition closely in regard to weeds, bugs, old flowers, and growth. Here's what I try to do:

- Deadhead as often as possible. Someone once said that should be a gardener's mantra. It's true. You don't want a plant wasting its life force turning faded blooms into seed heads (unless of course you need the seed).

- Clip back plants that have stopped blooming completely or are misshapen to promote new growth and flowers.

- Deal with pests and diseases as soon as you notice them. Start with the most environmentally friendly before you bring out the toxic stuff. Start with a hard water spray with the hose, a soapy water bath, hand-picking bugs, or cutting off diseased leaves.

- Stake tall plants before wind, rain, or their own weight damages them.

Stay on top of weeds. Why feed and water weeds? Wouldn't you rather your perennials get the water and nutrients in the soil? Mulch will slow them down but you'll still need to pull out some.